[Dr. Lin Yi-zhi] Development and International Trends in the Treatment of Sleep Apnea in Women

In our outpatient clinic, we often see men brought in by their wives or girlfriends, mostly because their partners can't stand their snoring and want medical help. However, we rarely see female patients seeking treatment. But is snoring only a problem for men? And is sleep apnea only a problem for men?

Looking back at past literature, the New England Journal of Medicine pointed out in 1993 that about 241 TP3T of middle-aged men and 91 TP3T of women suffer from sleep apnea[1]. In 2012, a European study pointed out that there are actually more female patients than imagined. About 501 TP3T of the 20-70 age group has sleep apnea problems; 141 TP3T of patients aged 55-70 have severe sleep apnea. If the patient is obese, the number of severe sleep apnea can be as high as 301 TP3T[2].

Since the statistical data shows a considerable proportion, why don't we encounter so many female patients in clinical practice? We can explore this from several aspects.

- Unladylike image

Basically, snoring itself carries a negative image. Telling a girl that she was snoring in her sleep is just as embarrassing as pointing out that she farted. So, basically no one would be so tactless as to tell their partner the truth directly. Therefore, girls are usually not told about snoring. Even if others do hear it, they are usually close friends and family who dare to tell them. Studies have found that, unlike male patients, female patients usually go to the doctor alone, which more or less shows that female patients feel more ashamed and uncomfortable about snoring than male patients[3]. However, for doctors, there is one less witness who can provide information on whether snoring or even breathing cessation was observed, thus one less piece of effective evidence to help with diagnosis.

- Symptoms differ greatly between men and women

For the assessment of sleep apnea, the most commonly used tool by physicians in the clinic is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), which is a questionnaire used to quickly assess the patient's symptoms.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) has a maximum score of 24 points. It is generally defined as follows: below 8 points is normal, 8-10 points is the gray zone, 10-12 points is mild sleepiness, and above 12 points is excessive sleepiness. For men, the most common symptoms are 1. snoring 2. witnessed apneas 3. excessive daytime sleepiness. However, women are more likely to present with headaches, anxiety, depression, insomnia, palpitations, nightmares, even hallucinations, and restless legs. If only questionnaires are used to assess female patients, that is, male symptoms are used to assess female patients, it is easy to exclude the patient from sleep apnea[4], or even transfer them to other departments for treatment, thus delaying the time for proper medical treatment.

- Differences in sleep structure

Compared to men, women take longer to fall asleep. If a couple goes to bed at the same time, the husband is already fast asleep while the wife is often still asleep. Even if the wife later snores or has sleep apnea, the husband is already asleep and therefore cannot observe whether the person next to him is sleeping normally, just like women do [5]. In addition, once a woman falls asleep, she is usually less likely to wake up, and her brain waves show more slow waves (deep sleep). In terms of the timing of sleep apnea, men tend to experience it during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, while women experience it during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep [6]. In terms of the sleep process, NREM sleep is the sleep establishment period, while REM sleep is the sleep transition period. Because the timing of these events is different, the damage to the brain is also different, and the resulting symptoms will also be different.

From an anatomical and physiological perspective

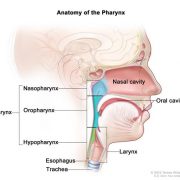

A study using MRI to assess women found that women have shorter tongues, shorter soft palates, shorter airways, and less soft tissue in the larynx [7]. Generally speaking, a shorter airway should be more prone to collapse, but why are there more male patients in clinical practice, and why are their symptoms more severe?

In fact, men's oropharynx is longer and softer, and their tongues are larger, thicker, and positioned further back. This makes the larger airway more prone to collapse, which can lead to sleep apnea during sleep.

Another important difference is the distribution of adipose tissue. We all know that obesity is a risk factor for sleep apnea, and the more severe the obesity, the more severe the sleep apnea. This phenomenon applies to both male and female patients. However, interestingly, female patients with the same degree of sleep apnea are often more obese than male patients[9]. And with the same BMI (assessing the degree of obesity), male patients often have higher average weight, adipose tissue, and neck circumference. A study that used MRI to assess the structural differences between men and women found that this phenomenon occurs mainly because female patients have less laryngeal fat and neck soft tissue in patients with the same degree of obesity[10]. A narrower airway is naturally more prone to obstruction or collapse.

- female hormones

Female hormones have the ability to maintain the patency of the upper respiratory tract and promote respiration. For example, progesterone stimulates chemoreceptors to enhance gas exchange when the concentration of carbon dioxide in the blood is high or the concentration of oxygen in the blood is low, and also increases the muscle tone of the upper respiratory tract[11]. In addition, hormones also affect the distribution of body fat. Postmenopausal women have more adipose tissue, and fat is more likely to appear in the upper body. In postmenopausal women, we found that the genioglossus muscle tone was low, but after two weeks of hormone replacement therapy, there was a significant improvement[12].

- Changes during pregnancy

During pregnancy, women are at increased risk of developing sleep apnea, mainly due to the growing uterus, which raises the position of the diaphragm and thus alters the breathing mechanism[13]. In addition, during pregnancy, the neck circumference increases, nasal patency decreases, and laryngeal edema increases, all of which contribute to the increased risk of sleep apnea. Studies have also found that snoring during pregnancy increases the likelihood of pregnancy-induced hypertension and intrauterine growth retardation[14].

- Other related studies

We all know the importance of sleep; good sleep leads to better energy. But are there other benefits for women? The answer is yes. In 2013, a study conducted by the well-known cosmetics company Estée Lauder at a university hospital found that when women don't get enough sleep, they are more prone to accelerated skin aging, reduced skin repair caused by environmental factors (such as UV light and environmental toxins), and an overall less attractive facial appearance.

- Treatment

Compared to male patients, female patients generally experience milder sleep apnea, but to date, there are no studies on different treatments for different genders. Current treatment strategies are similar to those for male patients.

For patients diagnosed with sleep apnea after multichannel sleep physiology (PSG), it is recommended that an ENT specialist first assess the airway, including endoscopy, CT scan, and X-ray, to check for any significant obstruction in the upper airway. Surgery can be used to improve the condition first, followed by positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, which often yields good results.

- International Trends

Sleep apnea is not a gender-specific disease like benign prostatic hyperplasia or ovarian cancer; it can occur in both men and women. Therefore, we should stop using male symptoms to assess women. Questionnaires, data assessments, and treatments should place greater emphasis on individual differences.

When we encounter patients in the clinic whose partners complain that their snoring is so loud that it is affecting their sleep, we need to not only care about the snoring patient, but also assess whether the other person also has sleep apnea problems.

When female patients experience insomnia, low mood, palpitations, nightmares, or even hallucinations, we don't just assess whether they are going through menopause or have related mental illnesses such as depression. We also need to assess whether their airways are narrowed or whether they have sleep apnea. This requires collaboration among otolaryngologists, psychiatrists, neurologists, rehabilitation specialists, and obstetricians and gynecologists. Only through team-based treatment can we reduce misdiagnosis and provide patients with holistic healthcare.

Reference:

- Young, T., et al., The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med, 1993. 328(17): p. 1230-5.

- Franklin, KA, et al., Sleep apnoea is a common occurrence in females. Eur Respir J, 2012.

- Quintana-Gallego, E., et al., Gender differences in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a clinical study of 1166 patients. Respir Med, 2004. 98(10): p. 984-9.

- Baldwin, CM, et al., Associations between gender and measures of daytime somnolence in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep, 2004. 27(2): p. 305-11.

- Valencia-Flores, M., et al., Gender differences in sleep architecture in sleep apnoea syndrome. J Sleep Res, 1992. 1(1): p. 51-53.

- O'Connor, C., KS Thornley, and PJ Hanly, Gender differences in the polysomnographic features of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2000. 161(5): p. 1465-72.

- Anttalainen, U., et al., Women with partial upper airway obstruction are not less sleepy than those with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath, 2013. 17(2): p. 873-6.

- Lin, CM, TM Davidson, and S. Ancoli-Israel, Gender differences in obstructive sleep apnea and treatment implications.

- Sleep Med Rev, 2008. 12(6): p. 481-96. Jordan, AS, et al., Respiratory control stability and upper airway collapsibility in men and women with obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol, 2005. 99(5): p. 2020-7.

- Mohsenin, V., Effects of gender on upper airway collapsibility and severity of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med, 2003. 4(6): p. 523-9.

- Tremollieres, FA, JM Pouilles, and CA Ribot, Relative in age and menopause on total and regional body composition changes in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1996. 175(6): p. 1594-600.

- Popovic, RM and DP White, Upper airway muscle activity in normal women: in uence of hormonal status. J Appl Physiol (1985), 1998. 84(3): p. 1055-62.

- Weinberger, SE, et al., Pregnancy and the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis, 1980. 121(3): p. 559-81.

- Macey, PM, et al., Heart rate responses to autonomic challenges in obstructive sleep apnea. PLoS One, 2013. 8(10): p. e76631.

Article source: Dr. Lin Yizhi, Department of Otolaryngology, Shuang Ho Hospital